Primitive Scent

Once man had discovered fire, he quickly learned that burning some types of wood, resins and herbs, released pleasant aromas and everything that was pleasant the primitive people used to please the gods. This practice was adopted by the Egyptians who, through specific rituals, burned different aromatic substances at different times of the day. The perfume’s role in religious rituals was dominant until the 16th century B.C. From then on, especially between the years 1580 and 1085 B.C., perfumes were used in two ways: either burned in the form of incense or applied on the body through perfumed balms and oils for medical, but also cosmetic purposes. This appealed to the Egyptian women who began to frequently use the products as weapons of seduction. It is said that Cleopatra was a specialist in this art, but also in the art of making her own perfumes. In fact, the Egyptians began to use their vast knowledge in this area to create the oils necessary to embalm the dead, a practice that they dominated like no other. From their contribution to the history of perfume also resulted some of the first glass perfume bottles.

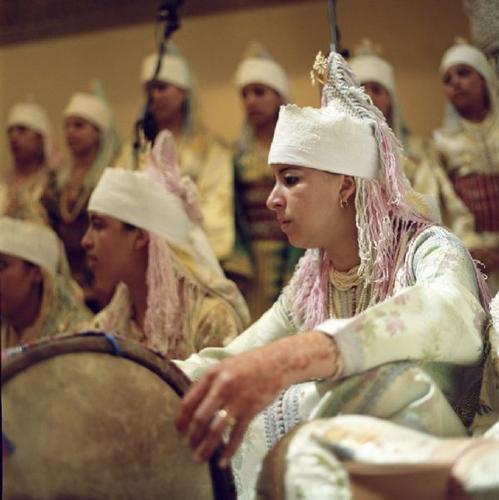

Arabic Scent

by Shaheen Darr

Arabic perfumes are an exotic and rich combination of incense and oils but without an alcohol base that is normally used in Western perfumes. Their fragrances are strong and spicy but unique and there is bound to be one that will appeal to your senses.

For Muslims the use of alcohol is avoided so natural products like rose, jasmine, lilies, sandalwood, musk and citrus fruits were used to create beautiful smells. The oil from the flowers was extracted by a distillation process and with the advent of Islam and the love of perfume that Prophet Muhammad had, “halal” perfume production spread even more.

Incense and fragrant herbs were burnt for fragrance, and rose water was and is very popular in Muslim countries. Attar, as it is called, can be combined with sandalwood, musk and amber to create oriental or Arabic scents. Even today you find rosaries or tasbees which have prayer beads that have been perfumed with rose water. As you touch the beads the smell of rose water fills and enhances the atmosphere around you. Exports of flowers from Egypt form the base of many perfumes used in European cities like Paris.

There are some other natural sources that are commonly used to make Arabic perfumes. The first is Oud which originates from the Aquilaria trees found in India and South East Asia. The wood found inside these trees gets a particular mould which gives it a unique fragrance. When you use Oud on your skin, the initial scent is quite strong but over time it becomes more subtle and is quite lasting. You can either use the wood or the Oud oil and this is burnt so that the smell from the smoke that emanates from it can linger around the house or on your clothing.

Then there is Bukhoor which are pieces of woodchips called Agarwood which have been scented with fragrant oils. Both Oud and Bukhoor are burnt in special oil or charcoal burners to create fragrant smoke. A piece of lit charcoal is placed in the burner and small pieces of Bakhoor are placed on this burning charcoal. If you leave the smell to travel around a room with the windows shut, the smell will linger on in the room for quite a while. These days electric burners are used instead of the traditional charcoal burners. The smell of Bukhoor signifies special occasions like weddings, and its fragrance helps to create feelings of wellbeing and pleasantness in social gatherings or in private homes.

Arabic perfumes leave a distinctive smell in most Muslim homes and in the shopping malls or souks of Middle Eastern countries. The exotic names used for Arabic perfumes add to their overall appeal as do the elaborate and exquisite presentation boxes in which they are sold.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X2Etg6p2IuE]

MYRRH AND FRANKINCENSE

Myrrh

Myrrh is the dried oleo gum resin of a number of trees from the Commiphora or Dhidin species of trees. The Myrrh trees are found as either small or low thorny shrubs that grow in rocky terrain. Like frankincense, myrrh resin it is produced by the tree as a reaction to a wound that has broken through the bark and into the sapwood. The trees are bled in this way on a regular basis.

When left on the tree, myrrh is waxy and brittle, but after the resin is collected into large bales it becomes a dry, hard and glossy substance that can be clear or opaque, and vary in colour. Depending on aging, this colour can range from yellowish to almost black, with white streaks.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=orenXYeCz2o&feature=related]

Frankincense

Frankincense begins its journey by being tapped from the very scraggly but hardy Boswellia tree. This is achieved by slashing the bark and allowing the exuded resins to bleed out and harden. These hardened resins are known as tears. There are numerous species and varieties of frankincense trees, each producing a slightly different type of resin. Differences in the soil and local climate will create even more diversity of the resin, even within the same species.

Frankincense has been one of the world’s most treasured commodities since the beginning of written history. At its peak its value rivaled that of gold, the rarest silks, and the most precious of gems. Ironically, it is but a milky-white resin produced by a scrubby, unlikely looking tree, genus Boswellia. There are twenty-five known species of Boswellia, each creating a water-soluble gum-resin with its own distinctive fragrance and medicinal properties.

Frankincense trees require an arid climate where moisture is provided by morning mist. The few ideal environments in the world for this small prized tree are found in Southern Arabia (Oman and Yemen), India, and Northern Africa (Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Kenya). Further, frankincense trees require a limestone-rich soil and are mostly found growing on rocky hillsides and cliffs, or in the dried riverbeds below. Harvesting can be a very dangerous task.

| Frankincense trees grow to about 20ft. in height (8m) with branches often beginning near its base. The common Oman, Aden (Yemen), and Somalia species, B. sacra / B. carteri, produce small yellow-white colored flowers with five petals, while the African B. papyrifera and B. thurifera produce small pale-red flowers. Each are a favorite among bees and produce small fruits which are fed to livestock. But it’s the trees’ resin that’s been treasured for thousands of years for its aromatic and medicinal uses. |

Frankincense resin begins as a milky-white sticky liquid that flows from the trunk of the tree when it’s injured, healing the wound. The Arabic name is luban, which means white or cream. It’s also known as olibanum, and its essential oil is often called “Oil of Lebanon.” It’s commonly recognized western name, frankincense, is said to have originated from the Frankish (French) Knights of the Crusades who treasured it in large quantities.

Frankincense resin flows when a tool called a mengaff is used to scrape about a five-inch section down the trunk of tree. The tree is marked and the harvester returns in two weeks to scrape what has become hardened frankincense resin from the tree. Resins which fall to the ground are collected on large palm leaves placed when first tapping the tree. The process repeats itself for about 3 months during harvesting.

Frankincense trees are ideally harvested twice per year, from January to March and again from August to October. The trees benefit from rest periods and produce finer quality resin when taken care of properly. Collected resins are aged for about twelve weeks and are then brought to the world’s markets. Finer resins are opaque white, semi-translucent white with shades of lemon or light amber. The exceptions are B. frereana which is used as chewing gum and is best soft and translucent lemon colored with golden hues, and B. serrata of India which is best golden to golden-brown. India’s B. serrata is highly prized and extensively used in Ayurvedic medicine.

Recent studies by an international team of scientists, including researchers from Johns Hopkins University and the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, have indicated that burning frankincense resin (Boswellia) helps to to alleviate anxiety and depression. The University of Munich found the anti-inflammatory properties of frankincense very effective as a treatment for joint pain and arthritis. The famous eleventh-century Arabian physician, Avicenna, recommended its cooling effects as a remedy for infections and illnesses that increase the body’s temperature. Greek and Roman physicians used Frankincense in the treatment of a great variety of diseases. Frankincense remedies appear in the Syriac Book of Medicine, ancient Muslim texts, and in Ayurvedic and Chinese medical writings.

Frankincense is also a natural insecticide and was used in ancient Egypt to fumigate wheat silos and repel wheat moths. In Arabia, the smoke of burning frankincense resin is used to repel mosquitoes and sand flies. Researchers have found that burning frankincense indoors improves the acoustic properties of the room. Dioscorides described how the bark of the tree was put into water to attract fish into nets and traps. In ancient Egypt the resin was a key ingredient for embalming their dead.

Frankincense in summary, is one of nature’s most cherished gifts. Whether you desire the pleasure of its pure resin for incense or its precious essential oil for aromatherapy, cosmetics or perfume, you can find a diverse line of high quality frankincense resins and oils here at our online store.

(Frankincense and Myrrh; A Study of the Arabian Incense Trade – by Nigel Groom)

Instructions on Burning Oud/Bakhoor/Lubaan:

Things You’ll Need:

Bakhoor

Electrical or charcoal incense burner

Charcoal discs

1Close all the windows in the house to make sure that no perfumes will escape the room.

2Turn on the electrical incense burner until it indicates that the plate is very hot. Proceed to Step 4 for burning the bakhoor. If you are using a traditional charcoal burner, begin with Step 3.

3Burn the charcoal discs in a separate container until they start to glow. You can use ceramic pottery, special metals or anti-burn plates.

4Place the charcoals in the designated place in your charcoal incense burner.

5Place the bakhoor chips on top of the electric plate or on top of the charcoal discs, depending on which type of incense burner you are using.

6Allow enough bakhoor to burn so that the smoke fills the room with a clear fragrance, but not so much as to use up too much of the oxygen in the room.

7Directly expose clothes to the smoke for three minutes to perfume them.